The results of the BTI 2020 in the context of COVID-19

In most of the 137 developing and transformation countries examined by the BTI 2020, COVID-19 will exacerbate the very weaknesses that have marked the negative balance of the last decade: a lack of rule of law, limited political rights, fiscal instability and rising social inequality.

Currently, the coronavirus pandemic is gripping large parts of the world. It is neither foreseeable how fast and far COVID-19 will spread, nor how long the resultant economic and social crisis will last until a vaccine is developed. What is clear, however, is that it will severely strain and probably overburden the often poorly developed health care systems of many of the 137 developing and transition countries examined by the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI), and will have far-reaching economic and social consequences. Some experts are already predicting that many countries will be set back many years in their development and that hundreds of millions of people are at risk of falling back into extreme poverty. This is an unprecedented stress test for the stability of political institutions and the governance capacity of the states affected by the pandemic.

The current handling of the crisis and its future repercussions suggest that the pandemic will exacerbate the very weaknesses that have marked the negative balance of the past decade identified by the BTI 2020.

Erosion of democracy

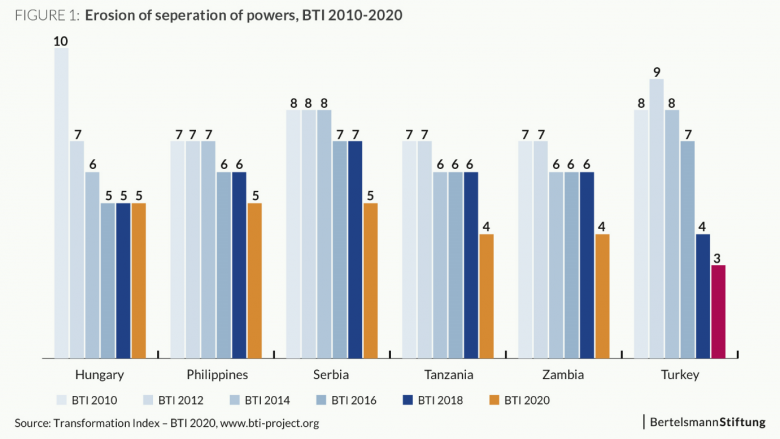

COVID-19 may contribute to increasing the concentration of power in the executive branch and further undermine the rule of law, accompanied by severe restrictions on political rights such as freedoms of assembly and expression. The current, crisis-related approval of an expansion of executive powers comes at the end of a decade in the course of which 60 of the 128 states examined by the BTI already in 2010 have already experienced a sometimes massive erosion of the separation of powers. In several countries, increasingly authoritarian heads of state now have the opportunity to further expand their already overstretched powers and, in the course of monitoring curfews and preventing fake news, to silence unwanted opposition voices.

The Hungarian example illustrates this problem: on March 30, Parliament adopted a self-disempowering emergency law by a two-thirds majority of the ruling Fidesz party that allows Prime Minister Viktor Orbán to govern by decree to deal with the crisis, extend the state of emergency indefinitely and suspend or deviate from existing legislation. This is combined with draconian sanctions for spreading misleading information and obstructing the fight against the pandemic and provides the government with extensive opportunities to further restrict freedom of expression and silence public criticism.

Even though the Hungarian undermining of the separation of powers represents the most serious case of democracy erosion to date, several governments are already moving in a similar direction, especially regarding restrictions on freedoms of expression and assembly. In addition to Hungary, the BTI 2020 particularly identifies Serbia, the Philippines, Tanzania and Zambia as candidates for slipping into authoritarianism. In these countries, the rule of law has already been undermined to a worrying extent in recent years, and if the concentration of executive power continues in the wake of the Corona crisis, their separation of powers is also in danger of falling below minimum democratic standards, as has already happened in Turkey.

The looming economic and social disaster

COVID-19 will trigger a massive health, economic and social crisis. Unlike in Europe, many developing countries are only just beginning to be hit by the full force of the pandemic, but the economic and social impact has been felt by their economies and especially by the most vulnerable members of society for some time.

Most of the 137 countries surveyed by the BTI 2020 do not have sufficient financial resources to contain COVID-19 or to implement economic stimulus packages. Even before the pandemic, a global debt crisis was threatening, and since then this scenario has become much more likely. Many countries are more heavily indebted than at any time since the 1980s. Massive over-indebtedness could result in a wave of national bankruptcies as the corona virus spreads. By mid-April, more than 100 governments had already applied to the International Monetary Fund for financial aid.

In addition to the lack of fiscal policy options for financing crisis containment and economic recovery, there are two further problematic aspects that make successful pandemic control in many countries unlikely:

For one, the medical infrastructure in most countries is so poorly developed that their capacities will very quickly be overstretched even with a moderate infection rate. For example, even under normal conditions, South Africa’s comparatively well-developed health care system, compared to other African countries, is already at the limit of its capacity with over seven million HIV-infected people.

Also, given the lack of hygienic, socio-spatial and management capacities in most countries, the infection rate cannot be kept under control once the epidemic has broken out. The Indian example, where millions of migrant workers carry the virus from the overcrowded cities back to their villages, illustrates that in the face of the daily struggle for survival, the call for “social distancing” will go unheard.

Life at or below the poverty line is part of daily experience for most people in developing countries. In the BTI 2020, 76 of 137 countries have a very low level of socio-economic development, rated at 4 points or less. Thus, in more than half of all countries examined by the BTI, poverty and inequality are widespread and indicate firmly established patterns of exclusion. Despite a general decline in extreme poverty rates, social inequality has increased over the past decade.

A major problem in this context is the small size of the formal sector in most countries. Even though the informal sector represents a safety valve for the unemployed, it is significantly less productive, less well paid, less accessible in terms of welfare policies and hardly protected by labor law at all. The social vulnerability of the population working in the informal sector is therefore particularly high and, as in the case of India with well over 80 percent of informal workers, is threatened by the corona crisis to increase dramatically. In this respect, the pandemic is about to evolve into a global social crisis of unprecedented magnitude.

Poor governance in times of crisis

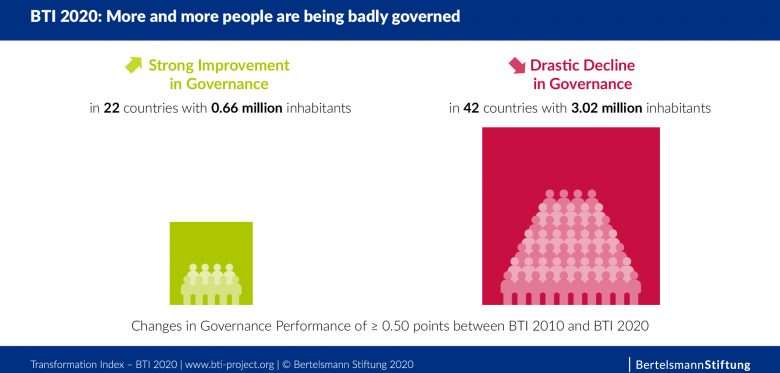

Against the background of the acute threat of major political, economic and social disruption, it is particularly problematic that many governments in developing and transformation countries are inadequately equipped for these major challenges. The current Transformation Index of the Bertelsmann Foundation paints a worrying picture and shows that the quality of governance in many countries has declined significantly over the past decade. These include populous and economically powerful countries such as Egypt, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria and Turkey.

In view of the need for a crisis strategy supported by society as a whole and coordinated internationally, it is particularly alarming that that the consensus-oriented aspects of governance such as conflict management or the willingness to cooperate internationally are declining very sharply.

Existing ethnic, religious or regional cleavages are often instrumentalized and deepened, so that the polarization of societies has increased worldwide over the past decade. Since 2010, the ability or willingness of governments to mediate and defuse conflicts has declined in 49 countries, particularly in Brazil, India and Turkey.

At the international level, too, the consensus-building aspects of governance have lost considerable weight, especially in Central America, the Middle East and in East-Central and Southeast Europe. Regional political power struggles and illiberal alliances have significantly impaired cooperation with external supporters and in the bilateral and multilateral framework. It is precisely the regional willingness to cooperate, which generally is rated quite highly, that has declined sharply in the BTI 2020. This points to the problematic perspective that in many places the response to the corona pandemic will be characterized by nationalistic self-interest and isolationism.

But other, more positive scenarios are also conceivable. On the one hand, authoritarian-populist governments in particular have so far failed in their crisis management, so that their disenchantment could result in a strengthening of more rational and consensual policy elements.

In addition, it is quite possible that a comprehensive crisis could lead to increased solidarity within society, strengthening civil society self-help and cooperation against the grave social consequences of the pandemic. Among the few democracy indicators that have developed positively in the BTI over the past ten years is the increased ability of civil society in many countries to self-organize and to cooperate.

Finally, before the spread of the virus reaches its peak in most countries, there is currently still the possibility of mitigating the impact of the crisis somewhat through significantly increased international cooperation. In recent weeks, the first promising steps have been taken to support developing countries, from temporary debt relief by the IMF and initiatives to strengthen the World Health Organization to aid packages worth billions. However, this will not be enough by far; support measures need to be introduced faster, in a more coordinated fashion and on a much larger scale. In view of the threat of famines of “biblical proportions”, which the United Nations World Food Programme is fearing in the absence of stabilization and support, it will be essential that the repeatedly emphasized political will for international cooperation quickly results in action. Then this crisis could also be an opportunity for a revival of multilateralism.