Endgames: Why Militaries Forsook Bouteflika and Al-Bashir, but Not Maduro

Massive peaceful protests are the ultimate endgame for autocrats: If all other means have failed, the incumbent’s political survival hinges on the loyalty of the military. In 2019, presidents in Algeria, Sudan, and Venezuela learned this the hard way.

When Algerian President Bouteflika announced to run for a fifth term, the masses flooded the streets. The military finally stepped in and pressured the president to resign. Similarly, after a month of countrywide protests, the Sudanese military dethroned long-time ruler Omar al-Bashir in a coup d’état. In Venezuela, however, the military has kept the regime alive despite ongoing protests.

Why do militaries react differently to protests in autocracies? Why do some stay loyal and defend the incumbent with brute force, while others defect either by staging a coup or by shifting loyalty to the opposition? From 2015 to 2019, researchers from Heidelberg University studied military reactions to peaceful mass mobilization in the “Dictator’s Endgame” project. At the heart of the project is a global dataset of all 40 endgames between 1946 and 2014.

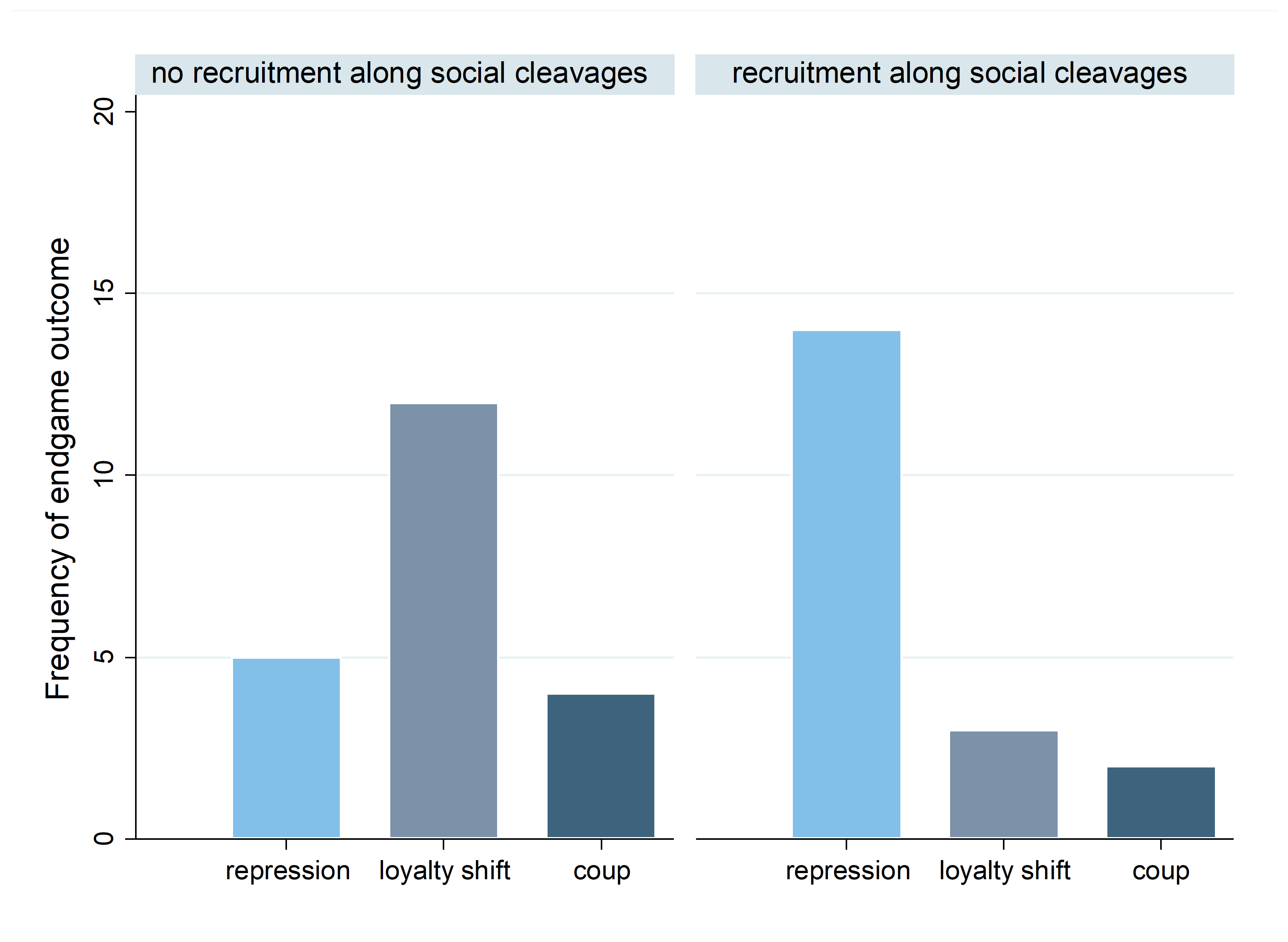

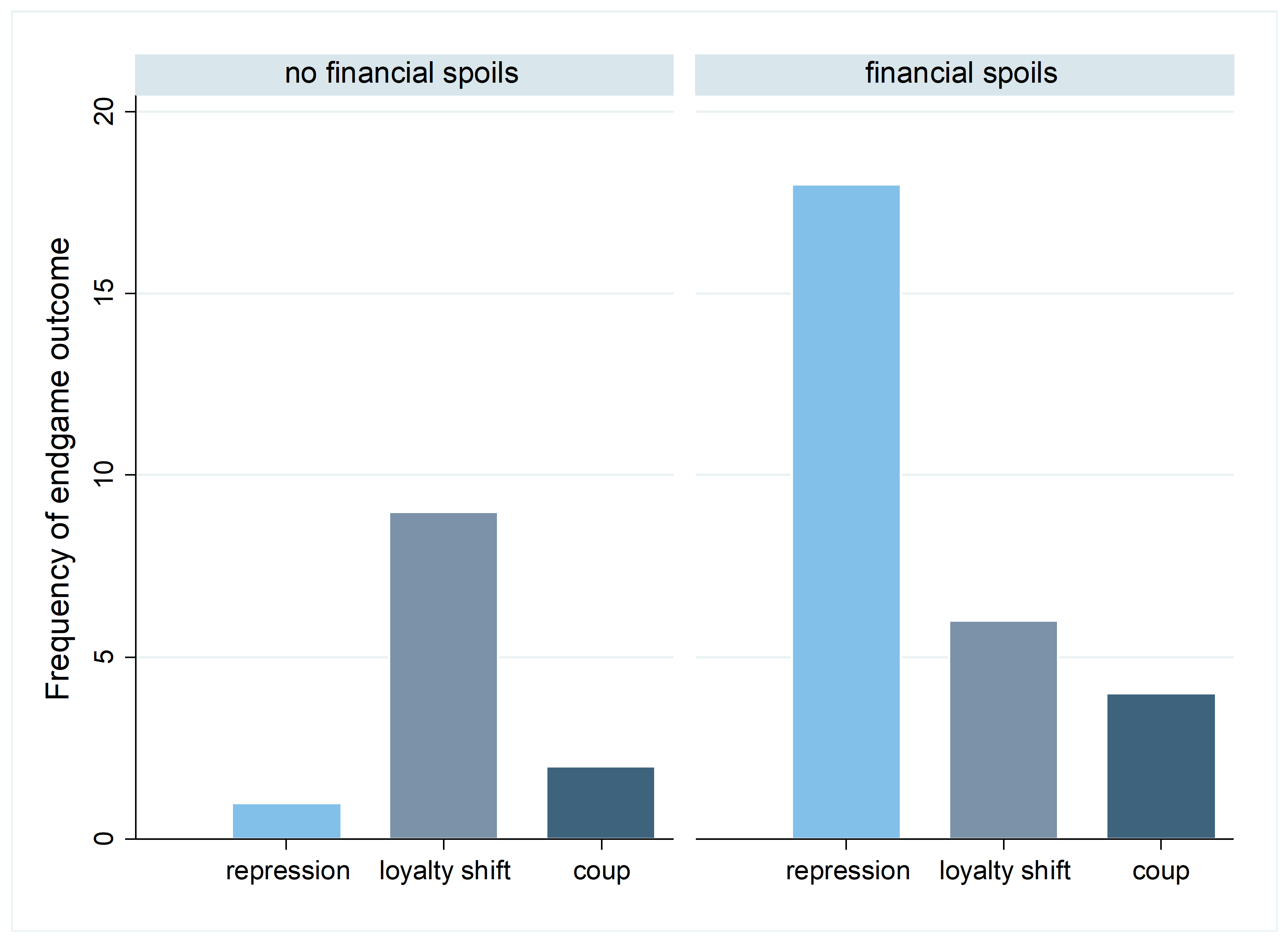

In short, the project provides two main takeaways: First, among many factors deemed important for the military’s reaction, two are key. Most military organizations that repressed protests were recruited along religious, ethnic, or other politically salient cleavages (see figure 1). Moreover, loyal militaries enjoy privileged access to financial spoils, such as comparatively large budgets and economic perks (see figure 2).

Second, the military’s decision always comes down to a simple cost-benefit calculation: What serves best the material and political interests of the military? In general, autocrats endure endgames if they have vested the military’s interests in the status quo. Militaries are therefore seldom advocates of political change for normative reasons. If they switch sides to the opposition, it is an act of self-interest rather than wholehearted support for democracy.

New endgames in Algeria, Sudan, and Venezuela

The 2019 endgames in Algeria, Sudan, and Venezuela echo these findings. In Algeria, military leaders decided to push the president of the edge. Given the military’s sweeping privileges, its move to forsake Bouteflika comes unexpected at first glance. Algeria had the highest military budget on the African continent and “the ‘deep state’ (i.e., the army and security forces) seem[ed] to take all relevant decisions with little democratic control“(BTI Country Report Algeria 2020). Yet, these privileges were at stake when protests threatened the incumbent regime. Removing the president offered security elites an opportunity to steer the uncertainty and safeguard their privileges beyond the Bouteflika era. Moreover, the crisis provided the military with a momentum to rid itself from rivals inside the ruling coalition. Most prominently, the late president’s brother Said Bouteflika, reportedly the clandestine puppet master behind the ailing Bouteflika, has recently been convicted by a military court.

In Sudan, the survival of al-Bashir’s regime hung in limbo at least since 2013, when mass protests over devastating living conditions erupted. The dictator had faced increasing criticism, not only from students, union leaders and political activists, but also from within his own party, the National Congress Party. From the military’s perspective, transition waited just around the corner. It was afraid of what might follow once 76-year-old al-Bashir had left office: Perhaps a loss of influence, as the military’s formerly strong political and economic weight had begun to slowly cede to powerful rivals in the security branch? Democratic transition with a more marginal role in the state apparatus? Prosecution for its human rights violations? “How to handle the unknown” must have been the central line describing the dilemma prior to the coup. Staying loyal to al-Bashir or staging a coup must have appeared as a choice between the devil and the deep blue sea. Both options would bear risks. Nevertheless, countering this unpredictability meant to preemptively intervene, moderate the transition phase, and consolidate the military’s position within the political system.

In Venezuela’s chaos, elites play a high-level stakes game for survival. President Maduro’s political survival depends on his ability to feed the clientelist networks created by Hugo Chavez, which include the top echelons of the military that have been primed to support whoever commits to the Bolivarian Revolution. In a way, the military’s support is less about Maduro and more about the continuity of his predecessor’s legacy. While he never served himself, Maduro learned from Chavez about the importance of keeping the military close. With that in mind, he continues to expand the military’s role in politics by appointing loyal officers to an increasing number of political positions. This strategy is not intended to provide the military with political power, but to keep officers economically secure. In the face of unprecedented economic decline – a “miracle in reverse” (BTI Country Report Venezuela 2020) –, allowing the military to oversee lucrative economic sectors raises the stakes to defect; it reminds officers that abandoning their cash cow would translate into an uncertain economic future.

Militaries and prospects for democratic development

In endgames, militaries do not only seal the political fate of authoritarian incumbents. Their reaction also alters the chances for democratic development. Evidence from the Endgame project shows that military repression prolongs authoritarian rule. Coups, too, seldom entail democracy. Among all endgames, those that were decided by military loyalty shifts have the highest chance to pave the way for a transition toward democracy.

How did military reactions in Algeria, Sudan, and Venezuela affect the outlook for democratization? In all three countries, sustainable democratic development is unlikely anytime soon. In Algeria and Sudan, militaries turned their backs on long-time rulers for selfish reasons, not for the sake of democracy. In Algeria, the military leadership’s probable plans have worked out. Though the military’s defection granted protesters a minimal victory in ousting the president, the regime has – at least until now – avoided a fundamental change from its authoritarian past and opaque inner workings. In Sudan, the military agreed to set up a transitional council that includes both civilian and military figures. Yet, already now General Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo, head of the paramilitary Rapid Support Force, has risen as new strongman from within the security apparatus. In Venezuela, things are not expected to turn around anytime soon. As long as the military believes that they need to fear what a potential democratic turn would mean for their economic position and Maduro continues to pay their bills, defection is just not a rational alternative.